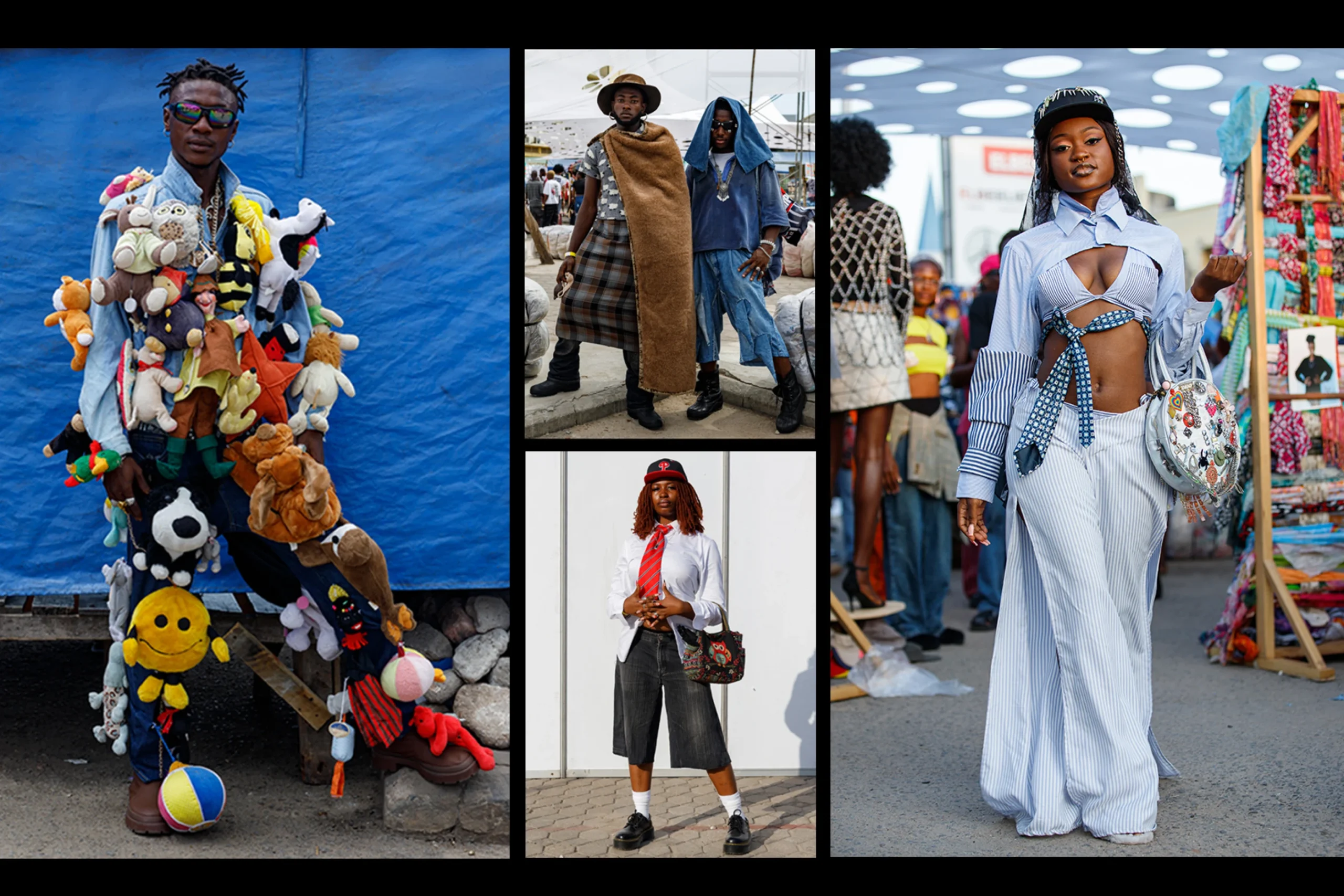

In Ghana’s capital, a bustling secondhand clothing market sees early morning shoppers sifting through heaps of garments, hoping to find a bargain or a designer piece among the low-quality apparel imported from the West. Meanwhile, at the other end of the street, an upcycled fashion and thrifting festival sparkles with style. Models strut down a makeshift runway, showcasing outfits made by designers from discarded materials sourced from the Kantamanto market, including floral blouses, denim jeans, leather bags, caps, and socks.

Richard Asante Palmer, one of the designers at the annual festival organized by the Or Foundation—a nonprofit focused on environmental justice and fashion development—explained, “Instead of letting textile waste clog our gutters, beaches, or landfills, I chose to repurpose it into something we can use again.”

Ghana is one of Africa’s largest importers of used clothing, receiving garments from countries like the UK, Canada, and China. Some of the imported clothing is in such poor condition that vendors dispose of them to make space for new shipments. On average, 40% of the millions of garments sent to Ghana each week end up as waste, according to Neesha-Ann Longdon, business manager for the Or Foundation’s executive director.

The Ghana Used Clothing Dealers Association reports that only 5% of bulk shipments to Ghana are immediately discarded due to being unsellable or unusable.

The festival, Obroni Wawu October—meaning “dead white man’s clothes” in the local Akan language—aims to disrupt the cycle of environmental degradation caused by Western overconsumption. Many of the worn-out clothes imported into Africa end up in waterways and landfills. In many African nations, secondhand shopping is common because it is more affordable than buying new items. It also offers access to designer goods that are otherwise out of reach for most people in the region.

The rapid growth of online shopping has accelerated this waste cycle. According to Andrew Brooks, a researcher at King’s College London and author of Clothing Poverty: The Hidden World of Fast Fashion and Second-hand Clothes, unwanted items in the UK are often donated to charity or stolen from donation bins, then exported to countries where demand for secondhand goods is high.

However, the reality is that Ghana’s population of 34 million and its infrastructure are unable to handle the sheer volume of textile waste flooding the country. Beaches across Accra are often littered with discarded clothes, while the city’s major drainage channels dump waste into the Gulf of Guinea.

“Fast fashion has become the dominant mode of production, marked by higher volumes of lower-quality goods,” said Longdon.

Fisherman Jonathan Abbey explained that his nets often capture textile waste from the sea. “Unsold clothes aren’t even burned, but just thrown into the Korle Lagoon, which then leads into the ocean,” he said. The overwhelming influx of secondhand clothing has led some African countries to voice concerns. For instance, in 2018, Rwanda raised tariffs on such imports, despite pressure from the US, in an effort to protect its domestic textile industry.

Last year, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni announced plans to ban the import of “dead people’s clothes.”

Experts, however, suggest that trade restrictions may not solve the problem of textile pollution or stimulate local clothing production in Africa, where profits are low and incentives for designers are limited.